James Cooper, Renewables Manager

Lochinvar

Accurate sizing of domestic hot water – avoiding oversizing

James Cooper, Renewables Manager for Lochinvar highlights the risks of oversizing DHW systems when applying CIBSE Guide G and how designers can avoid the problems it creates.

Oversizing of domestic hot water (DHW) systems can occur, particularly when applying CIBSE Guide G in projects such as student accommodation.

This oversizing is especially problematic for air source heat pump (ASHP)-based decarbonisation schemes, driving up capital costs, energy use, and feasibility risks.

A recent example from Lochinvar’s experience shows how the use of actual use data and modern control strategies can help to avoid these issues, reducing storage requirements without compromising performance.

Traditional methods for sizing domestic hot water (DHW) systems often rely on conservative assumptions and generic diversity factors. As a result, domestic hot water plant for air source heat pump systems is frequently oversized. This increases capital expenditure, operational expenditure and energy consumption. Often, in the case of decarbonisations projects, it can be the main reason the designs do not get past the feasibility stage.

A recent example from Lochinvar’s experience is an international student accommodation block in which the application of CIBSE Guide G resulted in a theoretical storage requirement exceeding 15,000 litres. However, by observing measured demand profiles and applying modern control technologies, this potential oversizing problem was avoided.

Domestic hot water production is a major energy and cost driver in high-occupancy residential buildings, particularly student accommodation. System oversizing is common due to standard design methods and a lack of building-specific usage profiles.

Oversizing not only increases plantroom footprint but also leads to higher installation costs, greater heat losses, unnecessary operational energy consumption and higher service and maintenance costs.

It is important to note differences between an international and domestic student accommodation block and plan your project accordingly.

The industry lacks an open source information portal to aid those responsible for system design and specification. Notably, international students in this context exhibited DHW usage patterns that differed significantly from domestic student cohorts, with earlier morning peaks and more continuous usage during the day.

In this example, the project was a multi-storey international student accommodation block. Key characteristics include:

- High-density occupancy with a fixed number of bed spaces.

- A population composed predominantly of international students.

- Communal kitchen and bathroom arrangements typical of modern student schemes.

Traditional DHW sizing with CIBSE Guide G

Using the standard methodology outlined in CIBSE Guide G, the scheme was initially calculated to require just over 15,000 litres of DHW storage.

While conservative, this approach assumes generic occupant behaviour and peak simultaneity factors that tend to favour oversizing. For heat pump-driven systems, such oversized volumes have several negative consequences:

- Increased capital cost due to larger storage vessels.

- Higher installation complexity and plantroom space requirements.

- Increased weight because of higher storage requirements, which can be particularly important in existing buildings.

- Elevated standing heat losses.

- Greater energy consumption as large volumes of water must be maintained at temperature.

Every building type exhibits unique DHW behaviour. Student accommodation, hotels, care homes, and build-to-rent schemes all have different peak patterns driven by resident demographics and operational culture.

To improve accuracy in system sizing, the industry should consider the following practices:

- Monitoring of DHW usage in existing developments to establish robust datasets.

- Engagement with clients and operators early in design stages to understand expected patterns of occupancy and behaviour.

- Differentiation of user groups, such as domestic vs. international students, whose habits can impact peak demand by several thousand litres.

By moving away from one-size-fits-all sizing, designers can reduce unnecessary system oversizing and improve the overall efficiency of DHW plant.

This is particularly important where low-carbon heating technologies are being applied. Traditional gas-fired systems can meet large instantaneous peaks through high kW input. However, air-source heat pumps cannot be economically sized to match these instantaneous capacities. Instead, designers often increase storage volume to offset reduced heat input.

While this strategy can be effective, it also introduces risk:

- Undersized storage → insufficient DHW during peak draw-off.

- Oversized storage → excessive energy use and wasted hot water.

Finding the optimum balance between storage capacity and heat input is therefore crucial.

Optimisation with controls

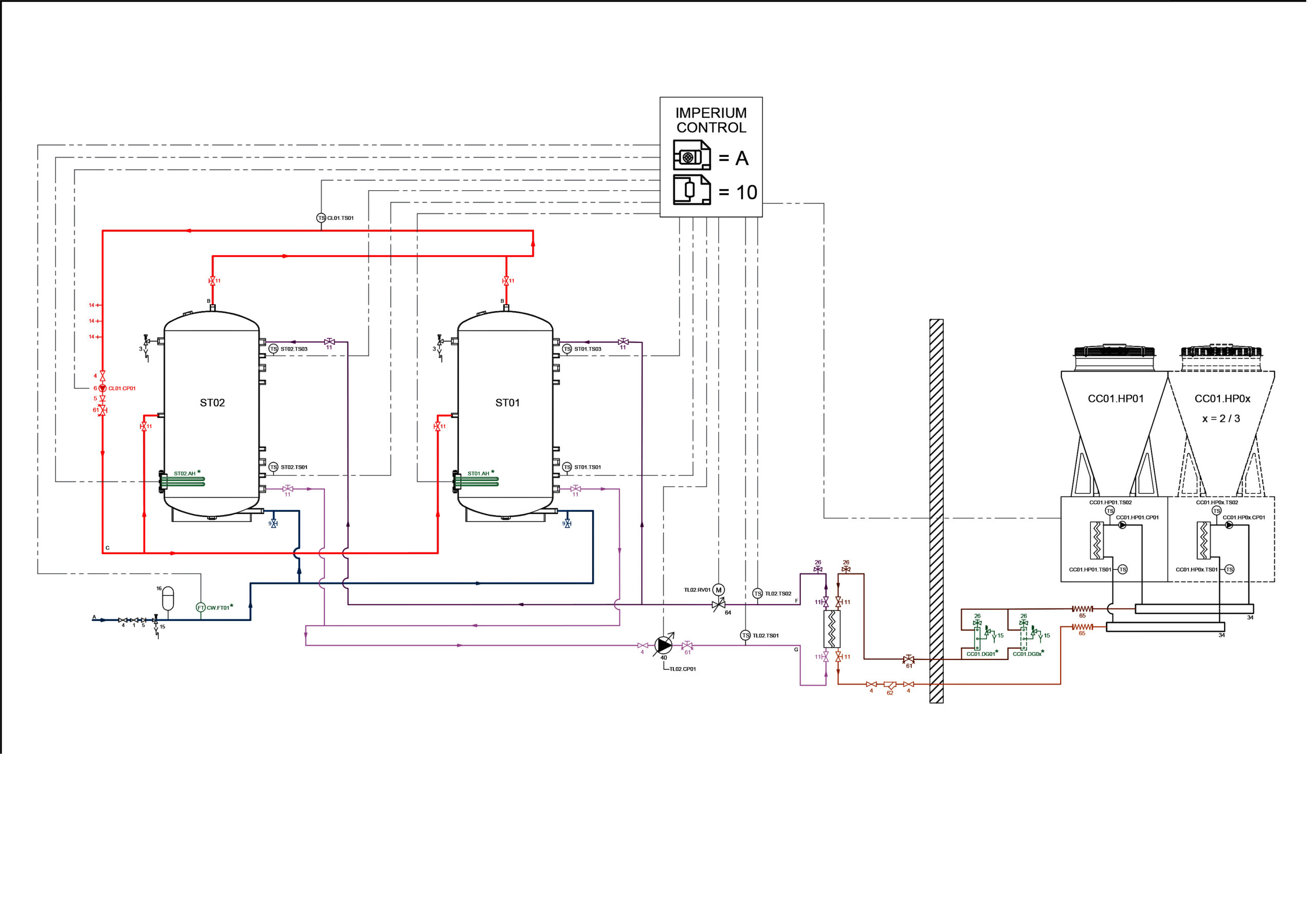

Lochinvar’s Imperium control system introduces advanced management of DHW production with one-pass (OP) and multi-pass (MP) parameters.

These control strategies allow for:

- More efficient utilisation of stored hot water.

- Faster recovery based on real-time demand.

- Reduced reliance on excessively large buffer volumes.

- Destratification of DHW vessels when ASHP operation begins.

- Maintenance of 5 or 10 degree building returns.

By applying Imperium’s OP/MP functionality to the student accommodation scheme, storage volume could be safely reduced to 7,500 litres, a 50% reduction from the traditional CIBSE-guided design, but without compromising supply resilience or user comfort.

This was achieved through:

- Tighter control of cylinder destratification.

- Enhanced modulation of heat pump output.

- Intelligent management of peak usage windows.

- Improved thermal efficiency during reheat cycles.

This case study demonstrates that traditional DHW sizing methods can significantly overestimate storage requirements, particularly in modern student accommodation.

However, through measured usage data and advanced control strategies such as Imperium’s one-pass and multi-pass functions, DHW storage can be optimised to reduce both capital and operational costs.

Oversizing of ASHP’s has tangible cost in terms of energy and carbon, as well as reliability implications for occupants. Accurate DHW sizing must be grounded in building-specific data, not generic assumptions. A shift toward data-driven DHW design will enable more efficient, decarbonised hot water systems, which is particularly important as the industry transitions to heat pump-based solutions.