Factors for healthy indoor air

Heather Wolfenden, Marketing, Communications, and Sustainability Director for Lindab UK , examines what we mean by ‘healthy’ indoor air and explains why good indoor air quality is vital for health and wellbeing.

What constitutes good and healthy indoor air? In this briefing we will consider the common internationally-recognised factors that define indoor air quality.

These factors are:

- Carbon dioxide levels

- Relative humidity

- Temperature

- Particulate matter

- Volatile organic compounds

Thanks to digitisation and sensor technology, these factors can now be continuously monitored in real-time, often integrated into building management systems or indoor air quality monitors. In other words: we can visualise the invisible.

How does carbon dioxide affect us?

Carbon dioxide is a naturally-occurring, odourless gas. Humans exhale it, but it is also produced by sources such as space heaters, clothes dryers and stoves. Indoors you’ll find much higher concentrations, often related directly to the number of people in a space. High levels are an indication of stale air which normally carries more particles and pollutants.

Levels which are too high can cause common symptoms such as headaches, drowsiness, difficulties concentrating and a decrease in productivity.

It is normally said that 400-800 parts per million molecules is a comfortable level of carbon dioxide. In well-ventilated buildings the concentration is usually around 600-800, and outdoors it is 350-450.

The best way to reduce carbon dioxide is to increase the airflow by increasing the operation of the ventilation system. If that is not possible, opening doors or windows is the easiest way, assuming that the outdoor air is clean, of course.

Relative humidity – an absolute health factor

Relative humidity indicates much moisture is in the air compared to the maximum it can hold at the current temperature. Warm air holds more moisture than cold air, so when the temperature rises, the relative humidity drops and vice versa. Low humidity is more common during winter when cold air heats up indoors, making the air dry.

Low moisture levels can irritate the mucous membrane and make people more likely to catch colds. It is also a common cause of nosebleeds, dry eyes, dry skin and sinus discomfort. High levels can cause moulds and other biological contaminants to thrive, resulting in symptoms like sneezing, runny nose, red eyes and skin rashes while also triggering asthma attacks.

Reviewing research, our overall assessment is that the right level is between 40-60 percent. It is a healthy level both for people and buildings, not causing mould, irritation or virus transmissions.

The easiest solution when the air is too dry is to lower the temperature. When humidity reaches levels which are too high, increase the ventilation to bring it back down. A dehumidifier can work for specific situations like water damage or to keep a very precise humidity. If you have very high humidity levels, you may want to check pipes and plumbing for water leaks.

Temperature – cold facts on a hot topic

Temperature is often the starting point when we talk about indoor air, and for good reason. It’s the most noticeable and adjustable factor. But what we’re really aiming for is thermal comfort, defined as “that condition of mind that expresses satisfaction with the thermal environment.”

What feels comfortable varies depending on age, clothing, health, and personal preference. While temperature plays a central role, thermal comfort depends on more than that. Radiant temperature, air movement, humidity, clothing, and activity level all contribute to how we experience comfort indoors.

At temperatures which are too high, humans get tired and have difficulty concentrating. Heat can also aggravate pollution. At temperatures which are too low, we find it difficult to do things physically. Both high and low temperatures can affect mental ability, work capacity, strength and mobility.

In general terms, a suitable indoor temperature in the summer is 23-26°C and in the winter 20-24°C. Summer indoor temperatures need to be warmer because light clothing and a big difference from outside temperatures would make us feel cold indoors otherwise. Body temperature naturally drops as you sleep so a cooler room, between 16-20oC makes it easier to fall and stay asleep.

In a larger space, with a group of people, there are tools available to calculate thermal comfort. Indicators such as Predicted Mean Vote (PMV), Percentage of Dissatisfied (PPD), and Draught Rate are used to estimate how people will feel in a space, whether it’s too warm, too cold, or affected by airflow. These help designers create environments that feel comfortable for most occupants.

Why particulate matter, matters

Particulate matter (PM) are dust particles that float in the air around us. These particles are created in nature by sandstorms and forest fires for example, but also by fossil fuels in vehicles, fireworks, tobacco smoke and so on. They are usually categorised according to their size, PM10 being particulate matter smaller than 10 micrometer (also termed microns), for example.

Most particulate matter usually gets stuck in the lungs, but small pieces can enter the bloodstream where they can spread to other organs. High levels of particulate matter may cause short-term health effects such as eye-, nose-, throat- and lung irritation, coughing, sneezing, runny nose and shortness of breath.

WHO guidelines recommend 5 micrograms of PM2.5 per cubic meter of air or less, annually. This can be measured with sensor devices for indoor spaces.

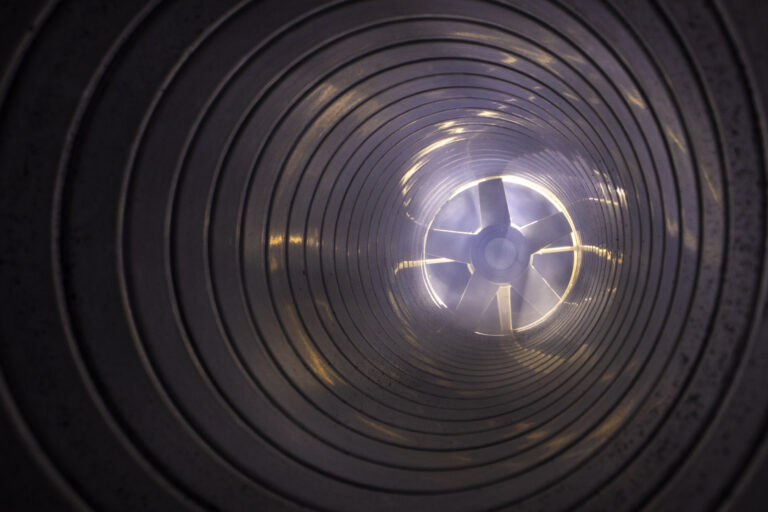

To avoid the risk of PM, make sure to keep your premises clean and dust free. If you have a ventilation system, the majority of the particles from outside can be removed. Make sure to have a good quality HEPA filter. For the particles already indoors, you may also consider buying an air purifier with HEPA filters.

The thousand gases of our everyday lives

Volatile organic compounds (VOC) is the collective name of thousands of different gases produced and used in our everyday life. Concentrations can be up to ten times higher indoors than outdoors27. They can be found in cleaning products and perfume, generated from day-to-day activities such as cooking and smoking but also come from furniture and various building materials too.

Possible short-term effects may include headache, nausea, cough and dizziness as well as nose, throat and skin irritation. Long-term effects may be hidden as seemingly normal symptoms, such as an allergic skin reaction or leg cramps.

An ideal concentration is 300 micrograms per cubic metre of air or less. Levels between 300 and 500 are considered acceptable, but above that, irritation and discomfort may begin to occur.

One simple action is to remove or reduce the number of products that emit these gases. Read labels to make sure which products have no or little emissions. Increase ventilation when using products that emit volatile organic compounds. If no ventilation system is available, opening doors and windows can serve as a temporary solution — helping to remove stale air and bring in fresh outdoor air.

Good air does us good

Creating environments with healthy indoor air helps us stay active, happy and high functioning. It is not all about reducing negative health effects – it is just as much about enhancing positive effects. Quite often they go hand in hand.

Outdoor air and its level of pollution occupy the thoughts of both the public and our governing bodies. It’s an important issue that is strongly connected to another matter we find is often forgotten or overlooked: indoor air. Considering how much time we spend indoors in the Western world, indoor air should receive at least as much attention as outdoor air, especially from a health perspective.